There have been many reports recently with headlines such as "

Why don't teen read for pleasure like they used to?" or "

Why aren't teens reading like they used to?" or "

U.S. children read, but not well or often: report". Most of the articles seem to reference

this article from Common Sense Media.

The statistics, quoted from Common Sense Media, are not encouraging:

- 53% of 9-year-olds vs. 17% of 17-year-olds are daily reader

- The proportion who "never" or "hardly ever" read has tripled since 1984. A third of 13-year-olds and 45% of 17-year-olds say they've read for pleasure one to two times a year, if that.

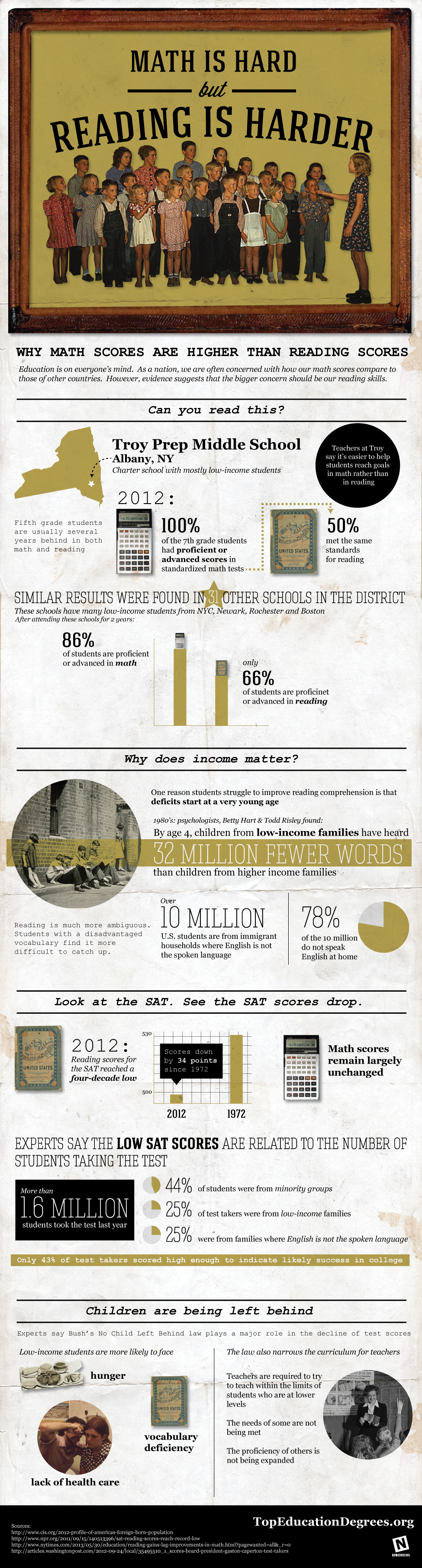

Two of the articles linked above also delve into reading proficiency. Did you know that only about 1/3 of fourth grade students read proficiently? Or that another 1/3 read at a below basic level?

As a citizen of the US, this concerns me. As an educator, a language educator no less, this concerns me. As a father of young boys, the oldest of which (2 years 8 months) loves being read to, this concerns me. As an individual who tries to set aside at least a little time for reading every day, this concerns me.

Most of the articles are fairly quick to single out rising rates of media usage as the primary culprit. Rates of television viewing have remained basically stable, but computer and handheld device screen time has risen precipitously. Most articles also mention, however mostly in passing, that screen time could be spent in reading activities.

I would also point to digital (visual) media as a primary culprit. Between watching a video and reading a story, watching videos has a lower cognitive load than reading, and people tend toward lower cognitive loads when they can. Watching videos is more immediately gratifying than the slower process or reading. Together, this is a near death sentence for pleasure reading.

People are quick to bring up the examples of the

Harry Potter series and

The Hunger Games, forgetting that these phenomena were not primarily a victory of reading. These were primarily social movements, drawing people in because all their friends were reading them, not due to an intrinsic interest in reading. It's that intrinsic interest that defines pleasure reading.

While many young people are reading via social media and the like, I would be loathe to call this pleasure reading. That type of reading only builds language skills for that arena: social media. The language used among peers does not readily transfer to the skills needed to comprehend or appreciate texts of fiction, non-fiction, biography, science, technology, etc.

It is popular today to hear people talk about "digital literacy" and to make trendy assertions that today's students are simply different and have different "learning styles" than students of the past. Reading, however, still does and will form the foundation of an educated society. Reading needs to to be a primary concern of parents, educators, and society as a whole.

Follow Matthew on Twitter

@MatthewTShowman